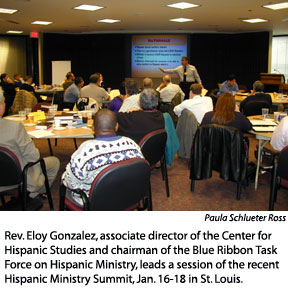

By Paula Schlueter Ross

Hispanic ministry is a “whole-church issue,” not just a “missions issue,” says Rev. Eloy Gonzalez, associate director of the Center for Hispanic Studies

So, issues of importance to Hispanic Lutherans — such as “inclusion,” national representation, immigration concerns, and language barriers — need to be shared with the church at-large, he says.

That’s why the Hispanic Ministry Summit, held Jan. 16-18 in St. Louis, brought together national LCMS executives and Hispanic ministry leaders to discuss the task force’s report and recommendations.

National LCMS executives “have really not ever been part of the full conversation” about Hispanic ministry, Gonzalez told Reporter. “So, we’re saying, ‘Hey, we want partners from the church to be part of this.’”

Hispanic ministry also has been seen historically in the Synod “as a responsibility of the Missions department only,” he said. “[Now] we’re saying it’s a whole-church issue.”

Executives from the Synod’s national offices — including those for schools, Black ministry, human care, pastoral education, university education, theology and church relations, district presidents, communications, and world mission — were invited to take part in the summit “to sensitize them and make them aware of the issues,” according to Gonzalez.

Those issues include:

- inclusion — Hispanics don’t feel like they have a role in a church body that projects more of a “ministry to Hispanics” than a “ministry with Hispanics.”

- isolation — Hispanics feel isolated from the national church because of language, economics, and culture. Synod periodicals are in English only, and they feel they have no “voice,” or representation, on the national level. (An LCMS World Mission staff position for Hispanic ministry was eliminated in 2003.)

- mission — Hispanic ministry is more than “planting churches,” and requires the same resources as other congregations to meet needs in evangelism, stewardship, education, fellowship, youth ministry, and human care.

- economics — many Hispanic families, particularly immigrant families, have limited incomes and limited resources to support their congregations, so is a part-time arrangement the only option for Hispanic-ministry pastors who may have to hold outside jobs to make a living?

- immigration — how can the church respond to immigrants, both legal and illegal?

Appointed by LCMS President Gerald Kieschnick last June, the task force is charged with determining the bes

Hispanics now number 44.7 million, or 15 percent of the U.S. population, and are the fastest-growing ethnic group in this country, according to the task force. Some 10,000 of the Synod’s 2.6 million members are Hispanic, and about 140 of the church body’s 6,000 congregations are involved in Hispanic ministry.

In a presentation that focused on the Synod’s “One Mission, One Message, One People” emphasis, Synod President Gerald Kieschnick shared results of a 2003 national survey of the religious affiliations of Hispanic people in the United States that shows the growth of Protestantism among second- and third-generation family members.

He urged summit attendees to share their faith with others, especially those outside the church, “planting the seed of the Gospel in the lives and hearts of people, one at a time.”

Integrating Hispanic people into the full life and ministry of the Synod, he said, “is a vision — it is not yet reality.” But, with a church body that is 96 to 98 percent white, there is an urgent need for the Synod to reflect a membership that is more like the U.S. population, Kieschnick said.

“By our baptism, we are one in Christ,” he said, adding that it is his “hope and dream … that our chu

Speaking again later in the summit, Kieschnick urged participants to use their God-given talents “to the greatest degree possible” and encouraged them to work toward the realization of Hispanic ministry goals. He also urged them to nominate Hispanic leaders to LCMS boards and commissions, including positions on the Board of Directors and praesidium.

“Is there any reason any one of them couldn’t be Hispanic?” he asked.

“Just do it,” he said, referring to Hispanic ministry. “Don’t wait for others to do it.”

Summit participants reacted to and discussed findings of the task force report, and prioritized a list of nine “methodologies,” or suggestions, to advance Hispanic ministry in the Synod.

Their top recommendations, in order of importance, are:

- placing a counselor for Hispanic ministry at the Synod’s national level to channel the concerns of Hispanic members to LCMS staff, boards, and commissions, and to share resources and information with Hispanic workers and congregations.

- making Lutheran schools more accessible to Hispanic families by “intentionally recruiting and supporting Hispanic students.”

- including and encouraging Hispanic people so they can share their knowledge and talents with the church at-large.

- reaching out to the needs of immigrants, both legal and illegal, and finding appropriate solutions to immigration concerns.

“There’s a great need for a national leader who can help bring together the folks who are out there in Hispanic ministry and lift up a vision among them

Hispanic Lutherans are anxious to get behind such a leader who can work full time for their causes, he said, and “make these things happen.”

“When you have a community that is somewhat marginalized and somewhat disconnected by culture and language from the church, it’s difficult for them to find leadership and to find a common direction,” he said. “So it’s a leadership issue, really, more than anything.”

The task force report, fine-tuned by summ