(Rated: G [Canada] and PG [MPAA] for thematic elements including medical descriptions of crucifixion, and incidental smoking; directed by Jon Gunn; stars Mike Vogel, Erika Christensen, Robert Forster, L. Scott Caldwell, Mike Pniewski, Tom Nowicki, Renell Gibbs, Haley Rosenwasser, Brett Rice and Faye Dunaway; run time: 112 min.)

A compelling film with a positive message

By Ted Giese

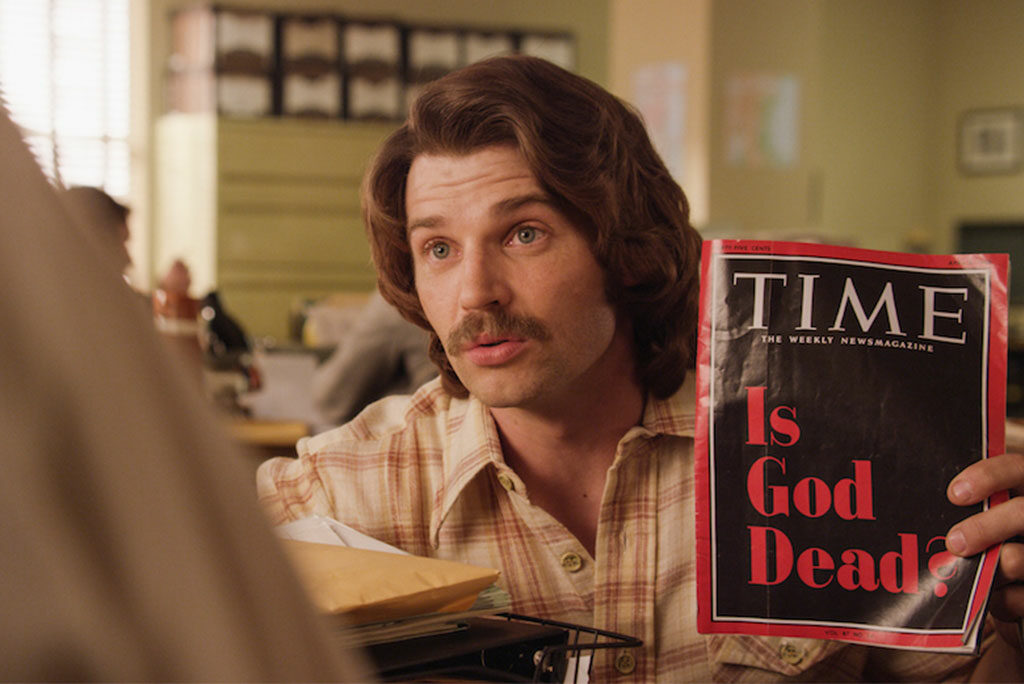

“The Case for Christ” is a docudrama detailing the story of a Chicago Tribune reporter, Lee Strobel (Mike Vogel), who attempts to disprove Christianity after his wife, Leslie (Erika Christensen), becomes a Christian following a “chance” encounter with a nurse (L. Scott Caldwell) who saves the life of their daughter (Haley Rosenwasser).

Sensing something more than coincidence at work — the right person (a nurse) in the right place (the restaurant) at the right time (a choking incident) — Leslie eventually accepts an invitation to go to church with the nurse. At church, she hears God’s Word and believes in Jesus.

Strobel, an award-winning journalist and avowed atheist, is beside himself at the news of his wife’s conversion to Christianity. The rest of the movie revolves around his work as an investigative journalist and his attempt to disprove Christianity so that his life can go back to the way it was before his wife’s conversion.

The film’s dramatic tension comes in the interplay between his bitter, alcohol-laden, downward spiral and his wife’s steadfast, yet tested, love for him.

Strobel’s investigation of Christianity hinges on one question: Did Jesus really die and then rise from the dead? If Jesus didn’t die, then there’s no reason to believe in a resurrection.

He wants to prove that Jesus’ death and resurrection are nothing more than legend, a really old lie, or maybe mass lunacy. As he begins working, he doesn’t consider that through his investigation he could end up making “The Case for Christ” as Lord and Savior.

Leslie Strobel’s coming to faith is more focused in her heart and personal experiences, whereas her husband’s old-school journalistic approach to every investigation — including his investigation into Jesus — focuses on the facts, while harboring deep suspicions.

He’s part of the “If your mother says she loves you, you’d better find another source to corroborate that story before it goes to print” school of journalism.

“The Case for Christ” quickly becomes a compelling story about a couple at odds over faith. It rings true because many couples experience the same tensions and stresses regarding faith and skepticism, even if a spouse isn’t a Chicago Tribune journalist.

As the film unfolds, a question emerges: Can the marriage weather this conflict, or is separation — or even divorce — on the horizon?

Christian viewers may be reminded of 1 Cor. 7:13-14, “If any woman has a husband who is an unbeliever, and he consents to live with her, she should not divorce him. For the unbelieving husband is made holy because of his wife, and the unbelieving wife is made holy because of her husband.”

In this case the unbelieving husband seriously contemplates divorce, but while he is frequently angry, unkind and drunk, he continues living with his wife and, much to his chagrin, begins noticing positive changes in her due to her Christian faith.

Some of the producers of “The Case for Christ” also worked on “God’s Not Dead 2” (2016) and some, like Elizabeth Hatcher-Travis and David A.R. White, also worked on “God’s Not Dead” (2014). But in this case, their efforts result in a better film.

A major complaint with the “God’s Not Dead” films was the poor treatment and development of the atheist characters. The screenwriters seemed to forget what St. Peter says when it comes to the task of apologetics (the reasoned defense of the Christian faith).

He says Christians should “always [be] prepared to make a defense to anyone who asks you for a reason for the hope that is in you; yet do it with gentleness and respect” (1 Peter 3:15).

While director Jon Gunn doesn’t sugarcoat Strobel’s faults and character defects in “The Case for Christ,” he presents a man who loves his daughter, struggles to love his wife, and even personally struggles to come to terms with his estranged father (Robert Forster).

Strobel also is portrayed as an honest journalist who, while good at his work, is willing to eat crow if he fails in his reporting. Essentially what viewers see is a fleshed-out character — not a flat, two-dimensional, cardboard cut-out or stereotype of an atheist.

This is a leap ahead when it comes to the way other faith-based films present nonbeliever characters.

As a film, “The Case for Christ” deals with its atheist characters fairly, one could even say with “gentleness and respect.” This is refreshing.

Lutheran viewers will want to be aware of the film’s strong, repeated emphasis on “decision theology” — that a person is saved when he makes a decision to accept and follow Jesus Christ.

That said, careful viewers will pick up on some elements that downplay making a personal decision for Jesus and better reflect the Small Catechism when it says in the explanation to the Third Article of the Apostles’ Creed: “I believe that I cannot by my own reason or strength believe in Jesus Christ, my Lord, or come to Him; but the Holy Spirit has called me by the Gospel, enlightened me with His gifts, sanctified and kept me in the true faith.”

Leslie becomes a Christian after hearing God’s Word. Receiving faith in this way echoes St. Paul: “Faith comes from hearing, and hearing through the word of Christ” (Rom. 10:17).

Another significant detail in this regard is the film’s use of an Old Testament verse from Ezekiel: “And I will give you a new heart, and a new spirit I will put within you. And I will remove the heart of stone from your flesh and give you a heart of flesh.”

After Leslie encounters this verse, she makes it her prayer for her husband.

Ultimately, while Lee Strobel wrestles against God with all his reason, strength and investigative drive, the film shows it is God who changes the investigator.

Ironically, just as he can’t investigate his wife’s way out of the faith, he can’t investigate his way into the Christian faith.

Overall, the film shows it was God who “called, gathered and enlightened” Strobel, and Strobel is portrayed as a man with the gift of a repentant heart.

Most Christian viewers familiar with popular apologetics won’t be surprised by the film’s ending: Lee Strobel is now a popular Christian apologist and author.

Although this film is a cut above other films in the faith-based genre (better script, acting, cinematography and design), it still hits a couple of snags.

First, because “The Case for Christ” is professed to be a “true story” and deals with questions and answers rooted in apologetics which center on a search for and a proclamation of what is true, viewers might expect a high level of accuracy in telling Strobel’s story.

A quick surf over to YouTube will find a number of videos of Strobel telling his story. When they are compared to the 2017 film, it will become apparent that some details have been altered and/or added for dramatic effect.

Depending on the purpose of “The Case for Christ,” this could easily become a major flaw.

By injecting Strobel’s true story with factually inaccurate details, skeptical viewers may be tempted to distrust the important truths concerning the life, death and resurrection of Jesus. That could be a problem if the purpose of the film is reaching agnostic, skeptical and atheist viewers with a personal story about a man who was where they are now.

If, however, “The Case for Christ” is intended only to encourage people who already believe — who, it is assumed, will not have their faith in Christ rocked by some dramatization of Strobel’s life — then perhaps adding fictional elements will not be an issue.

A really great film for everyone — believer and nonbeliever — would present both an unvarnished account of Strobel’s journey and a strong apologetic for Jesus’ life, death and resurrection. If viewers dig into the details of “The Case for Christ,” they will find it to be a strong film on the latter point and a good-but-weaker film on the former.

Viewers — both Christian and non-Christian — will have to come to terms with whether it’s important that the film’s details about Strobel’s life are accurate. Hopefully, this won’t be a distraction from the core message of God’s love for the world in Jesus Christ.

While overly sentimental and sappy in spots, “The Case for Christ” is a step in the right direction.

Aspiring Lutheran scriptwriters and directors can be encouraged by a film like this, even if they are critical of its flaws. It shows that the door continues to open wider and wider for telling new stories on film.

What would a similar, modern Lutheran entry into the faith-based genre look like? Better yet, what would it look like if it was not even categorized as “faith-based,” but mainstream?

Could someone make such a film successfully for both Christians and non-Christians?

Good questions to ponder after seeing “The Case for Christ.”

Unlike “The Shack,” which muddles up the Holy Trinity in an unchristian way, “The Case for Christ” is a Christian film with a positive message that clearly points to Christ Jesus while emphasizing that it is God who ultimately changes hearts.

Watch the trailer

The Rev. Ted Giese (pastorted@sasktel.net) is lead pastor of Mount Olive Lutheran Church, Regina, Saskatchewan, Canada; a contributor to the Canadian Lutheran, Reporter Online and KFUO.org; and movie reviewer for the “Issues, Etc.” radio program. Follow Pastor Giese on Twitter @RevTedGiese.

Posted April 11, 2017