By Uwe Siemon-Netto

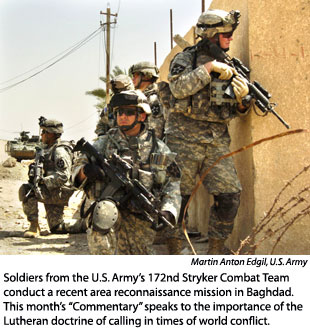

Evoking the Lutheran doctrine of calling has never been more imperative than in times of world conflict — in a word, now. The lives of millions of people and the survival of a democratic society, indeed perhaps of the United States as a free and unified nation, are at stake.

Those called to act responsibly and out of love for their fellow man are legion. They include media workers, political professionals, diplomats, policy makers, the military , intelligence officers and, most of all, the sovereign of the republic — the voters.

, intelligence officers and, most of all, the sovereign of the republic — the voters.

This column concerns three contemporary wars — the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan, and Israel’s war of survival against Hezbollah, the terrorist long arm of Iran.

It also relates to the ability of Americans to suffer protracted conflicts without chickening out when the going gets tough or the headlines become too repetitious. When that happens, as was the case in Vietnam, Cambodia, and Laos 30 years ago, millions die, are tortured and confined to “re-education camps,” as Communist death camps were euphemistically called. The blood of these millions is not merely on the hands of their executioners and torturers. It is also on the hands of those who abandoned them, and that includes American voters.

On the other hand, this column cannot dwell on the mistakes that might have been made when America involved herself militarily in Indochina or in the Middle East.

This columnist has no divine calling to second-guess the decision-makers. Perhaps it would have been, to name an example, expedient not to topple Saddam Hussein. Maybe he knew what he was doing when he slaughtered his own citizens or had their toenails pulled; maybe this was the only way to maintain order in the multi-ethnic and multi-religious madhouse he presided over. But to argue along such lines would be cynical and unbecoming of Christians. It would be like saying, “We should have left Hitler in power; at least he knew how to run the railroads on time.”

At any rate, Saddam is no longer in charge in Iraq, a nation now hopelessly mired in chaos. Now what?

Even if U.S. involvement in Iraq was a mistake, you can’t undo it by slinking way from its consequences, as little as you can “uncook” a badly cooked stew or “unraise” a badly raised child.

The Lutheran doctrine of calling does not attribute infallibility to our secular endeavors; we have to accept the fact that they are under sin like all our actions in the “left-hand kingdom,” as we Lutherans call the secular realm, and must use natural reason to solve problems as best we can.

Nobody can claim, for instance, that Israel is infallible and that Israel’s bombing of civilian dwellings in Lebanon is a godly thing. But then how does an imperfect military establishment, which is called to assure its nation’s survival, deal with the fact that Hezbollah fighters have stored their rockets in civilian homes, paying their proprietors $100 for accommodating the deadly ordnance destined to be lobbed on Jewish dwellings one day?

Oh, you didn’t know that? You didn’t know that by accepting Hezbollah’s money these civilians ceased to be non-combatants? Well, then you have not lived up to your calling as a citizen — the calling to inform yourself.

True, this detail wasn’t shown on commercial television, a medium whose sense of calling still seems under construction, which is why it keeps warping public opinion. But you could have read about it in responsible newspapers. And as sovereign of a free nation, as a voter, you do have a calling to enlighten yourself comprehensively before praising or condemning other countries for their actions.

Moreover, we all have a calling to draw proper analogies, such as this one: Would it not have been more humane if in World War II the Allies had behaved like Israelis today, warning civilians to run because their part of town was about to be bombed? As one who in his childhood was at the receiving end of British and American bombs, this commentator would have appreciated this courtesy instead of having to listen to the list of killed and maimed classmates during roll calls at school after each night of bombing.

The doctrine of calling gives us no option to extricate ourselves from unpleasant situations for the sake of our immediate comfort without considering the interest of others, including the next generation of Americans.

For this foreigner, the spectacle of U.S. Democrats turning against Sen. Joseph L. Lieberman (D-Conn.) because he had stood by his President in the war on terror is shocking news indeed. Even the Clintons have withdrawn their support from him, even though their positions on Iraq had been identical to his.

This behavior does not suggest an acknowledgment of calling but is an exercise of expediency. In the short run, it might serve these politicians’ purposes, but it cannot be seen as an act of neighborly love; for to a Christian the term “neighbor” applies to anybody, in Iraq as well as in the United States. If America abandons that country to bedlam and civil war, if Washington ultimately pulls tail and allows Iraq to fall into the hands of Islamist Iran, an evil power that will soon possess nuclear weapons, this might spell the end of the wonderful America so many of us love.

Such an act would make a mockery of democracy in that it would tell the world that Americans cannot be counted upon to sustain an armed conflict for more than two congressional terms, simply because self-interest would drive politicians to betrayal. Worse still, the world’s television cameras would savor the streams of blood brought about by the abandonment of Iraq. The outside world, forever critical of America, albeit foolishly, would now quite understandably hate it.

As a result, America would cease to exist as a moral world power, a nation with a calling. And one shudders to think what this would mean for this country’s internal peace, well-being, and ultimately its survival as One Nation Under God.

Dr. Uwe Siemon-Netto, a veteran international journalist, is scholar in residence and director of the Concordia Seminary Institute on Lay Vocation, St. Louis, and director of the Concordia Center for Faith and Journalism at Concordia College, Bronxville, N.Y.

Posted Aug. 31, 2006