By Paul L. Maier

My Sunday school teacher had to be a very patient person, since I regularly asked her questions about biblical events that missed the point of the story, so she claimed.

For example, I was pleased that Jesus could cure the cripple who had been let down through the roof at Capernaum. “But what did they do about

Up went her hands in dismay. “Ask your father!” she cried.

Once, though, she was not peeved. We were hearing the Passion story, and when we got to Good Friday, I asked, “Teacher, how could the crowds who sang ‘Hosanna’ to Jesus on Palm Sunday go on to scream ‘Crucify Him!’ just five days later?”

“Paul, at last you’ve asked a good question!” she responded. “People can be fickle, and change their minds quickly.” That held me for some years, even though I was still mystified that the crowd could shift that quickly.

Years later, when attending the seminary, I asked the same question in a class on the New Testament world. The professor smiled — a little patronizingly, I thought — and replied, “I think it’s obvious, Paul: those people were fickle. They changed their minds quickly when Jesus lost popularity during Holy Week.”

The same response! I’d wager that many readers of Reporter learned the same explanation, never mind that it carries with it a good dose of anti-Semitism, however unintentional: those fickle Jews!

I believe that the well-meaning Sunday school teacher and the erudite seminary professor were both categorically wrong.

Clarifying facts

For 20 centuries now, the Jewish role during that first Holy Week has been debated, a discussion too important for the limited space here. It is high time, however, to bury the concept of “the fickle Jew” and correct misinterpretations in our teaching and learning about what happened on Good Friday.

How could the Palm Sunday crowd ever have turned against Jesus when, contrary to so many claims, Jesus was not losing but gaining popularity during Holy Week? On Sunday the people shouted “Hosanna!” On Monday they and the Passover pilgrims cheered as Jesus cleansed the temple, since they also despised the commercialism practiced there by Annas, Caiaphas, and company. The first century Jewish historian Josephus and the Talmud report that the high priests regularly profited from the temple concessions and were cordially despised by the people.

On Tuesday and Wednesday the crowds smiled as Jesus trumped the silly questions posed by his opponents who were trying to trap him in dialogue. By Wednesday night, then, Jesus was more popular than ever.

On Maundy Thursday, therefore, He must really have “blown it” (in popular parlance) since this was the last day before the crowds presumably shifted their cry from “Hosanna!” to “Crucify!” But this won’t work. Jesus did not go into Jerusalem that Thursday morning, but spent a quiet day with His mother, Mary, and the disciples at the home of Mary, Martha, and Lazarus in Bethany. That evening they had a very private dinner party in an upper room in Jerusalem, launching what would become the longest meal in history: the Lord’s Supper.

The key verse: Luke 23:27

So when did Jesus lose his popularity? The fact is that He did not, as proven by the scene of Jesus dragging his cross to Calvary. In the most overlooked verse in the Bible, Luke 23:27, we read: “And there followed him a great multitude of the people, and of women who bewailed and lamented him.” The “people,” of course, were Jews, as proven in the very next verse. These are the “Hosanna” followers of Jesus who never changed their minds between Sunday and Friday.

Why, then, didn’t they intervene in Jesus’ behalf (if they even could have)? Since Jesus was arrested late Thursday night, they could not even have known about that arrest until Friday morning, when it was too late to crowd into Pilate’s courtyard since it was already filled with Jesus’ opponents. All they could do now was line the roadsides and weep as Jesus dragged his cross to Golgotha.

How, then, could Jews in general ever have been called fickle “Christ-killers” and been subject to centuries of anti-Semitism in the face of these weeping Jewish followers of Jesus on Good Friday? Later on, anti-Semitism might have developed because of the Jerusalem persecution of the early Christians, St. Paul’s struggles with Jewish opponents during his mission journeys, and the split between church and synagogue. But it should never have arisen because of Good Friday.

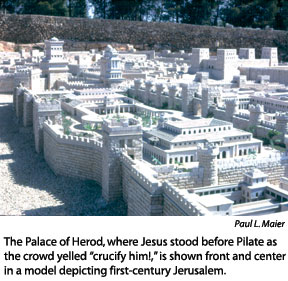

On the other hand, too many radical revisionists today are claiming that no Jews were involved on Good Friday, and that the Gospels have misled us. Yet this is equally mistaken. The New Testament has it exactly right: Jesus certainly did have Jewish opponents who wanted him dead and did yell “Crucify!” on that infamous Friday, but they were not the “fickle Jews” of Palm Sunday. Instead, they were a priestly directed claque from the Sadducean authorities who controlled the Temple — again, Annas, Caiaphas, and their coterie. They wanted Jesus terminated as a pseudo-Messianic figure who might lead a revolt and bring on the Romans. Josephus tells us that there were 10,000 in the Temple police alone. Less than 5 percent of that number would have been more than enough to crowd into Pilate’s courtyard and serve as a speech chorus of condemnation directed by Caiaphas and the priestly aristocracy of Jerusalem.

Bottom line, then: the “Hosannas” of Palm Sunday and the “Crucifys” of Good Friday came from entirely different Jewish crowds.

Necessary reinterpreting

Probably this is not the way we all learned and taught it, but this reading of the sources contradicts not one syllable of the Gospel record. Rather, it picks up on that important nugget of evidence that Luke supplied, tears away one large root of anti-Semitism, and makes the events of Holy Week that much more credible. Had more attention been paid to Luke 23:27, perhaps the pogroms of Medieval Europe and even the Holocaust might have been diminished. Certainly the countless debates — every 10 years — over perceived anti-Semitism in the Oberammergau Passion Play or e