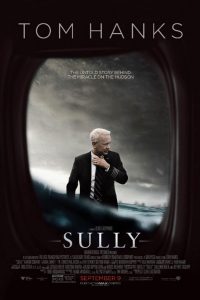

(Rated: PG [Canada] and PG-13 [MPAA] for some peril and brief strong language; directed by Clint Eastwood; stars Tom Hanks, Aaron Eckhart, Laura Linney, Patch Darragh, Jamey Sheridan, Michael Rapaport and Vincent Lombardi; run time: 96 min.)

From air to sea, in good hands

By Ted Giese

In “Sully,” Director Clint Eastwood tells the story of Captain Chesley “Sully” Sullenberger (Tom Hanks) who, with the help of his co-pilot Jeff Skiles (Aaron Eckhart), successfully executed a controlled water landing on the Hudson River on Jan. 15, 2009, saving all 155 souls on board US Airways Flight 1549. The film deals with that fateful day, the subsequent investigation and the personal pressures that come with suddenly being at the center of a major news event.

This is a “true story” film, and as far as that goes, appears to be a cut above other films in the “based on a true story” genre. It’s a genre Eastwood has tackled before with films like “American Sniper” (2014), where Eastwood delved into the psychological life of Navy Seal sniper Chris Kyle.

This is a “true story” film, and as far as that goes, appears to be a cut above other films in the “based on a true story” genre. It’s a genre Eastwood has tackled before with films like “American Sniper” (2014), where Eastwood delved into the psychological life of Navy Seal sniper Chris Kyle.

In “Sully,” Eastwood considers the psychological and emotional landscape of Sullenberger, who, like Kyle, was driven by duty and vocation. The film’s drama comes from contrasting the media and public admiration of a genuine hero with the realities of post-traumatic stress disorder; quiet, personal doubts; and the scrutiny of a Federal Aviation Administration investigation.

Where the film becomes untethered from actual events is in the compressed accident investigation — especially the initial interviews Sully and Skiles have with the National Transportation Safety Board (NTSB). In a 96-minute film there isn’t a lot of time to lay out with any level of detail a 15-month federal investigation. The film ramps up the tension with antagonistic and pensive attitudes from the NTSB investigators.

While it is routine to ask questions of a pilot concerning the last time they had an alcoholic beverage, if they’ve taken any drugs, had any health issues or personal stresses that could impact their ability to perform their work, how those questions are asked makes the difference between depicting a professional, dispassionate investigation and cold antagonism.

Audiences should take these initial investigation scenes with a grain of salt, considering they didn’t unfold as presented in the film and the nature of the NTSB meetings may be colored by Sully’s and Skiles’ personal reminiscences.

In a New York Times article, real-life NTSB investigator Robert Benzon, who was involved in the investigation but isn’t depicted in the film, clarifies that he and his colleagues “weren’t out to hose the crew,” hyperbolically adding that “there were no rubber hoses being brought out, no bright lights.” To be fair, Eastwood doesn’t include any rubber hoses or bright lights in his film, however, the work of the NTSB investigators is shown as less than sympathetic in the film’s first act.

In 2009, the water landing was dubbed “the miracle on the Hudson” and Sullenberger became a news-media saint. With serious journalists, news outlets and popular pulp entertainment shows reporting the story in exhausting detail domestically and internationally, it’s a genuine challenge for a filmmaker to tell a well-known story when the audience already knows the outcome.

To say that Eastwood can deliver a tense and suspenseful film is an understatement. He has proven again and again in films from “Gran Torino” (2008) to “Unforgiven” (1992) that he can take almost any topic and find the story’s underpinning human dimension. It’s safe to say that Eastwood is an actor’s director with his storied acting career in iconic films like “The Good, the Bad and the Ugly” (1966) and “Dirty Harry” (1971).

As a result, he is comfortable taking time to explore the faces of his actors, using their expressions both great and small, in the same way other directors might consider a landscape or action piece.

This is particularly evident in how Eastwood uses Tom Hanks’ performance in this film. In his portrayal of Sully as a man haunted by 208 seconds in the air where life and death hinged on every thought, Hanks’ acting is both restrained and natural. His face reveals every decision in those long, silent seconds after both engines of his plane failed at low altitude, as well as every second thought that followed during the sleepless nights and subsequent investigation.

Following Sully’s successful landing on the Hudson River, a man in the film comments how “It’s been a while since New York had any news this good … especially with an airplane in it.”

Released on the weekend of the 15th anniversary of 9/11, the events of that day in 2001 loom large in the background of the film, as they would have in the minds of the pilots on Jan. 15, 2009. No pilot before and certainly no pilot after 9/11 wants to be in a situation where he or she could hit buildings full of people.

New York City and 9/11 are part of the film’s fabric, but Eastwood doesn’t exploit them for cheap, visceral effect. Rather, in a mature and thoughtful way, he manages to evoke 9/11 in relation to Sullenberger’s story. Both Sully and Skiles are shown as men equally concerned for both the public, who trust pilots to do their jobs well, and for the passengers on the plane they are flying. These pilots are diligent men, striving to protect everyone by their choices and actions.

Christian viewers might ask if God is in the film. Two brief moments are worth watching for. The first involves prayer. It might be expected that Eastwood would linger on passengers praying in their seats as the plane falls, but he doesn’t. In the midst of the mad scramble for a plan of action after the bird strike and engine failure, air traffic controller Patrick Harten (Patch Darragh) — while desperately trying to help from the ground — has a brief prayer/exclamation to God. It passes as quickly as it comes, but it is there and he along with other characters express great relief when they find out Sully managed to save the lives of his passengers and crew.

In the second moment worth watching for, the audience sees briefly a bright-white-neon cross sign hung on the side of a building and carefully framed in the shot above the car into which Sully and Skiles are directed as events unfold after the water landing. Since the film isn’t told in a perfectly linear fashion, this scene comes before Harten’s prayer/exclamation and Eastwood appears to use the cross — the symbol of Christ’s saving work for all of humanity — to reinforce the fact that these pilots were the instrument of the flight’s deliverance from a sudden and evil death.

For those who fly regularly or who have family who do, a film like this reminds us to pray for pilots and for all the people involved in air travel. A hymn like “Eternal Father Strong to Save” (LSB 717, Verse 3) may come to mind:

“O Spirit, whom the Father sent

To spread abroad the firmament;

O Wind of heaven, by Thy might

Save all who dare the eagles’ flight,

And keep them by Thy watchful care

From ev’ry peril in the air.”

(And if the plane ends up in the water, the end of the first verse would certainly apply, “O hear us when we cry to Thee, For those in peril on the sea.”)

When Sully receives credit for his heroism, with humility he is quick to point out everyone else who played a part in those 24 minutes following the water landing who in their vocations helped in the rescue — everyone from his co-pilot, Skiles, and the rest of the plane’s crew to the Thomas Jefferson NYC ferry Captain Vincent Peter Lombardi (who portrays himself) and other ferry-boat captains and crew along with the NYCDP Scuba unit.

Eastwood’s film details how the human element made the difference, yet Christians watching will consider how it was men and women rising to the occasion within their vocations that produced the results that day, and how God, working by means of His creation in the world, was present but masked beneath their vocational work.

What benefit is there in a film like “Sully”? Is it simply a solid drama? An entertaining look at an event made popular by the media? Or can something more be contemplated?

Perhaps it can serve as a reminder for people to take to heart the work set before them — whether ordinary or extraordinary — that, in doing so, they will have a part to play in the lives of others. How does St. Paul put it in Titus? “Let our people learn to devote themselves to good works, so as to help cases of urgent need, and not be unfruitful.” A potential and imminent plane crash certainly counts as a case of urgent need.

“Sully” is worth watching and worth thinking about. Eastwood manages to make an intimate human story out of events most people only experienced through news reports and TV appearances.

The Rev. Ted Giese (pastorted@sasktel.net) is associate pastor of Mount Olive Lutheran Church, Regina, Saskatchewan, Canada; a contributor to the Canadian Lutheran, Reporter Online and KFUO.org; and movie reviewer for the “Issues, Etc.” radio program. Follow Pastor Giese on Twitter @RevTedGiese.

Posted September 15, 2016 / Updated September 17, 2016